Homes in neighborhoods that were “redlined,” a practice that began in the 1930s to prevent people of certain races economic classes from buying in certain areas, still have relatively low value compared to other homes in their respective cities, according to new research from Zillow.

Redlined areas were those that were rated as “hazardous” for mortgage lending by the Federal Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC). “Redlining” derives from when areas on maps were colored red to signify being high-risk for mortgage lenders.

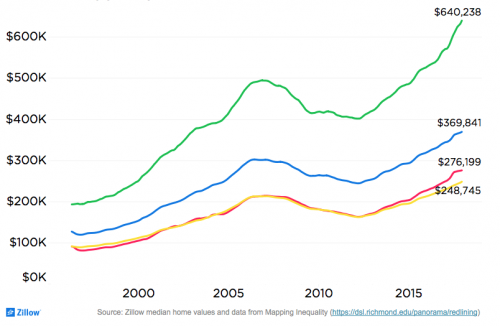

Despite the Fair Housing Act banning the practice in 1968, the economic repercussions of redlining can still be seen today. The national median value of a home in a formerly redlined area is $276,199, compared to a median value of $324,489 for homes in nearby areas that were never redlined — a 15 percent price differential.

The majority of residents in redlined areas were racial minorities, who were subsequently unable to obtain housing loans — making it virtually impossible to buy a home.

“The lasting impact of redlining is a striking example of how the kind of discrimination — financial and racial — codified nearly a century ago continues to affect homeowners and whole communities today,” said Dr. Svenja Gudell, chief economist for Zillow.

In Atlanta and Tampa, homes in neighborhoods that were once redlined are now worth less than half of the non-redlined homes in the area. Redlined homes in Atlanta have a median worth of $193,866, while the rest of Atlanta homes have a median worth of $428,813. Formerly redlined Tampa homes are valued at a median of $219,991, while their counterparts hold a median value of $482,141.

Though the Fair Housing Act prohibits discrimination in housing, a study by the Center for Investigative Reporting aims to prove that discrimination through mortgage lending persists, with lenders targeting racial minorities individually as opposed to entire neighborhoods.

“Redlining harms individuals and families by restricting their access to quality financial products and services as well as their opportunity to own a home and build wealth,” said Lisa Rice, president and CEO of the National Fair Housing Alliance. “It harms all members of the community by driving disinvestment and blight and continuing the unfortunate history of systemic economic oppression of marginalized groups by causing a decrease in home values.”